Hearing impairment

- Category: Diseases of the ear, nose and throat

- Views: 50045

Hearing loss is considered to be the most prevalent congenital abnormality in newborns and is more than twice as prevalent as other conditions that are screened for at birth, such as sickle cell disease, hypothyroidism, phynilketonuria, and galactosaemia (Finitzo & Crumley, 1999). It is one of the most common sensory disorders and is the consequence of sensorineural and/or conductive malfunctions of the ear. The impairment may occur during or shortly after birth (congenital or early onset or may be late onset) caused post natal by genetically factors, trauma or disease. Hearing loss may be pre-lingual (i.e., occurring prior to speech and language acquisition) or post-lingual (i.e., occurring after the acquisition of speech and language).

Since hearing loss in infants is silent and hidden, great emphasis is placed on the importance of early detection, reliable diagnosis, and timely intervention (Spivak et al., 2000). Even children who have mild or unilateral permanent hearing loss may experience difficulties with speech understanding, especially in a noisy environment, as well as problems with educational and psycho-social development (Bess et al., 1988; Culbertson & Gilbert 1996). Children with hearing loss frequently experience speech-language deficits and exhibit lower academic achievement and poorer social-emotional development than their peers with normal hearing.

Snoring and Sleep

- Category: Diseases of the ear, nose and throat

- Views: 50544

Snoring is noisy breathing during sleep. It is a common problem among all ages and both genders, and it affects approximately 90 million American adults — 37 million on a regular basis. Snoring may occur nightly or intermittently. Persons most at risk are males and those who are overweight, but snoring is a problem of both genders, although it is possible that women do not present with this complaint as frequently as men. Snoring usually becomes more serious as people age. It can cause disruptions to your own sleep and your bed-partner's sleep. It can lead to fragmented and un-refreshing sleep which translates into poor daytime function (tiredness and sleepiness). The two most common adverse health effects that are believed to be casually linked to snoring are daytime dysfunction and heart disease . About one-half of people who snore loudly have obstructive sleep apnea.

While you sleep, the muscles of your throat relax, your tongue falls backward, and your throat becomes narrow and "floppy." As you breathe, the walls of the throat begin to vibrate - generally when you breathe in, but also, to a lesser extent, when you breathe out. These vibrations lead to the characteristic sound of snoring. The narrower your airway becomes, the greater the vibration and the louder your snoring. Sometimes the walls of the throat collapse completely so that it is completely occluded, creating a condition called apnea (cessation of breathing). This is a serious condition which requires medical attention.

The thrombophlebitis

- Category: Diseases of the blood vessels

- Views: 51513

Thrombophlebitis (throm-boe-fluh-BY-tis) occurs when a blood clot blocks one or more of your veins, typically in your legs. Rarely, thrombophlebitis (sometimes called phlebitis) can affect veins in your arms or neck.

The affected vein may be near the surface of your skin, causing superficial thrombophlebitis, or deep within a muscle, causing deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Thrombophlebitis can be caused by trauma, surgery or prolonged inactivity. Superficial thrombophlebitis may occur in people with varicose veins.

A clot in a deep vein increases your risk of serious health problems, including the possibility of a dislodged clot (embolus) traveling to your lungs and blocking an artery there (pulmonary embolism). Deep vein thrombosis is usually treated with blood-thinning medications. Superficial thrombophlebitis is sometimes treated with blood-thinning medications, too.

The skin

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 79707

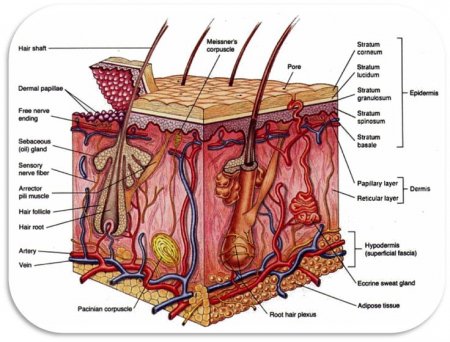

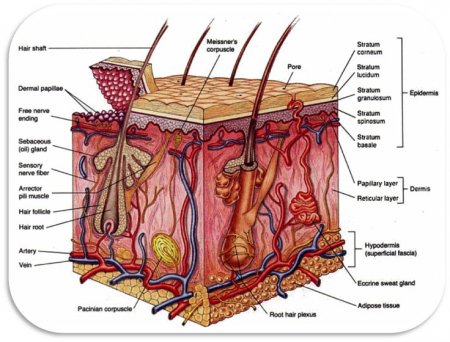

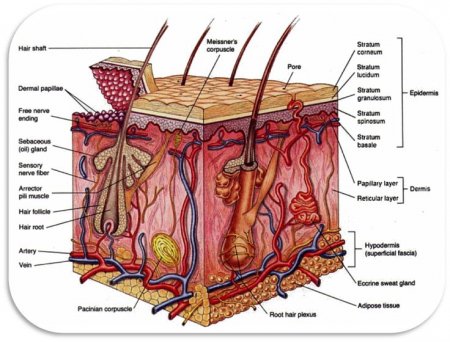

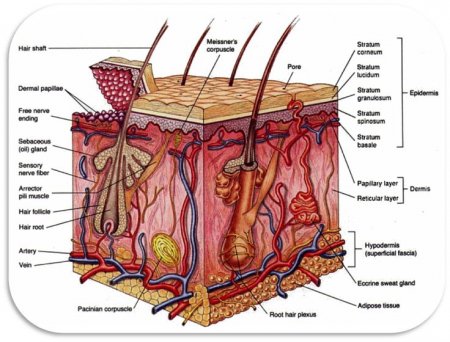

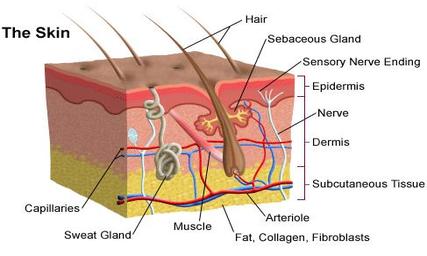

The skin is by far the largest organ of the human body, weighing about 10 pounds (4.5 kg) and measuring about 20 square feet (2 square meters) in surface area. It forms the outer covering for the entire body and protects the internal tissues from the external environment.

The skin consists of two distinct layers: the epidermis and the dermis. Each layer is made of distinct tissues and performs distinct functions to support the body. A third layer of tissue under the skin, known as the hypodermis or subcutaneous layer, is not truly part of the skin itself but connects the skin loosely to the underlying muscles and bones that make up the deeper tissues of the body. The epidermis is made of four to five layers of epithelial tissue that constantly grows from the inside out and replaces most of its cells every few weeks.

The hair

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 79164

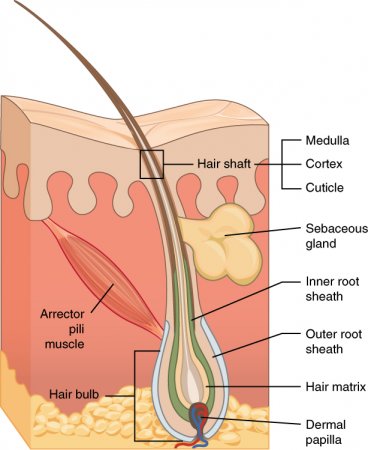

Hair is present on all skin surfaces except the palms, soles, lips, nipples, and various parts of the external reproductive organs; however, it is not always well developed. For example, it is very fine on the forehead and the inside surface of the arm. Each hair develops from a group of epidermal cells at the base of a tube-like depression called a hair follicle. This follicle extends from the surface into the dermis and may pass into the subcutaneous layer. The cells at its base receive nourishment from dermal blood vessels that occur in a projection of connective tissue, called the derma papilla, at the base of the follicle. As these epidermal cells divide and grow, older cells are pushed toward the surface. The cells that move upward and away from the nutrient supply then die. Their remains constitute the shaft of a developing hair. In other words, a hair is composed of dead epidermal cells.

The fingernails

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 79862

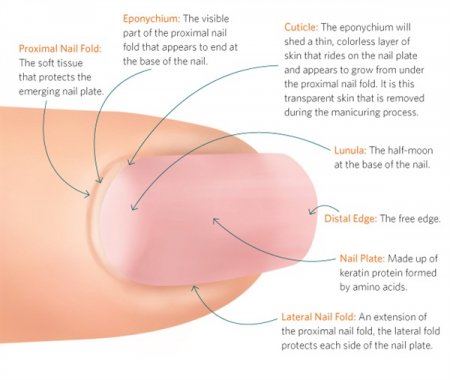

The fingernails are a sort of envelope composed of keratin, a tough protein, which cover the top of the terminal phalanges of a person's fingers. Nails are similar to the claws that can be found in other animals. Each nail is made up of a nail plate—this is the top of the nail. It is also made up of the nail matrix, a thin layer of tissue upon which the nail plate rests and the site of the cells that eventually become the nail plate. Each nail also has a nail bed—a layer of skin that connects the nail matrix to the hand. And lastly, each nail has the grooves that surround the nail matrix.

The integumentary system of the leg and foot

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 7841

The integumentary system of the lower extremities includes the skin, hair and nails of the legs, feet, and toes. The skin of this system is the first barrier against damage to the muscles of the legs, feet, and toes. Both men and women have hair on their legs and the tops of their feet, but this hair is somewhat thicker and coarser in men than in women. The toenails protect the toes from injury; they also enhance the sensitivity of the tips of the toes, although the nails themselves have no nerve endings.

The integumentary system of the arm and hand

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 9632

The integumentary system of the upper extremities (including the shoulders, arms, hands and fingers) includes the skin and hair, and nails of the upper extremities. The skin of the hands and arms (especially the hands) is more frequently exposed to sunlight and to environmental toxins than other parts of the body. Therefore, the hands are likely to show evidence of accumulated damage from these influences as a person ages.

The integumentary system of the lower torso

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 5624

The integumentary system of the lower abdomen and pelvis includes the skin and hair of this region. The skin of this system protects against damage to the organs contained within the abdomen. Additionally, the skin over the genitals is the first line of defense against sexually transmitted diseases and other diseases that affect these reproductive organs. Both men and women have hair on the lower abdomen that extends from the lower edge of the chest to the pubis. Hair in the genital region is known as pubic hair.

The integumentary system of the upper torso

- Category: Integumentary System

- Views: 5868

The integumentary system of the upper torso is made up of the skin and its appendages (such as the hair); its primary function is to protect the body from damage; it is also involved in temperature regulation and in the sense of touch. Upon exposure to sunlight, the integumentary system is also the primary vehicle for synthesis of vitamin D.