Stomach

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 748

The stomach is a vital organ in the digestive system that plays a crucial role in breaking down food and extracting nutrients from it. Located in the upper abdomen, the stomach is a muscular sac that can expand and contract as needed to accommodate food and aid in the digestive process.

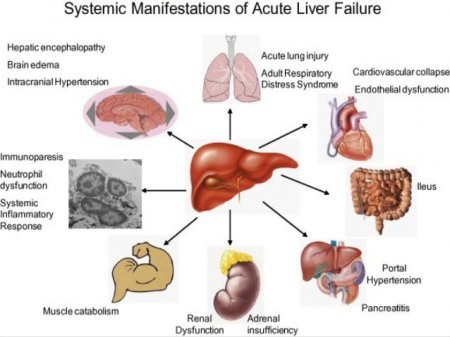

Acute liver failure

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 18997

Acute liver failure is a pathological condition with massive damage to liver cells and a violation of their functions. In severe form of the disease may occur a hepatic coma.

Infant reflux

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 56398

Infant reflux occurs when food backs up (refluxes) from a baby's stomach, causing the baby to spit up. Sometimes called gastroesophageal reflux (GER), the condition is rarely serious and becomes less common as a baby gets older. It's unusual for infant reflux to continue after age 18 months.

Reflux occurs in healthy infants multiple times a day. As long as your baby is healthy, content and growing well, the reflux is not a cause for concern.

Rarely, infant reflux can be a sign of a medical problem, such as an allergy, a blockage in the digestive system or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

GERD - Gastroesophageal reflux disease (Acid reflux)

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 55166

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic digestive disease. GERD occurs when stomach acid or, occasionally, stomach content, flows back into your food pipe (esophagus). The backwash (reflux) irritates the lining of your esophagus and causes GERD.

Both acid reflux and heartburn are common digestive conditions that many people experience from time to time. When these signs and symptoms occur at least twice each week or interfere with your daily life, or when your doctor can see damage to your esophagus, you may be diagnosed with GERD.

Most people can manage the discomfort of GERD with lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications. But some people with GERD may need stronger medications, or even surgery, to reduce symptoms.

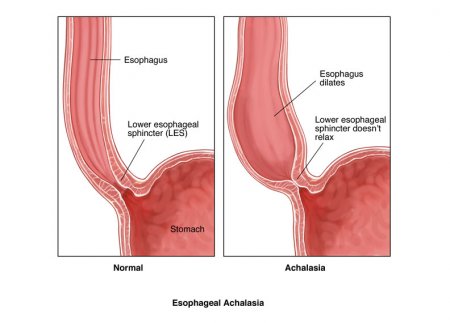

Achalasia

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 57659

Achalasia is a rare disease of the muscle of the esophagus (swallowing tube). The term achalasia means "failure to relax" and refers to the inability of the lower esophageal sphincter (a ring of muscle situated between the lower esophagus and the stomach) to open and let food pass into the stomach. As a result, people with achalasia have difficulty swallowing food. In addition to the failure to relax, achalasia is associated with abnormalities of esophageal peristalsis (usually complete absence of peristalsis), the coordinated muscular activity of the body of the esophagus (which comprises 90% of the esophagus) that transports food from the throat to the stomach.

The esophagus has three functional parts. The uppermost part is the upper esophageal sphincter, a specialized ring of muscle that forms the upper end of the tubular esophagus and separates the esophagus from the throat. The upper sphincter remains closed most of the time to prevent food in the main part of the esophagus from backing up into the throat. The main part of the esophagus is referred to as the body of the esophagus, a long, muscular tube approximately 20 cm (8 in) in length. The third functional part of the esophagus is the lower esophageal sphincter, a ring of specialized esophageal muscle at the junction of the esophagus with the stomach. Like the upper sphincter, the lower sphincter remains closed most of the time to prevent food and acid from backing up into the body of the esophagus from the stomach.

The upper sphincter relaxes with swallowing to allow food and saliva to pass from the throat into the esophageal body. The muscle in the upper esophagus just below the upper sphincter then contracts, squeezing food and saliva further down into the esophageal body. The ring-like contraction of the muscle progresses down the body of the esophagus, propelling the food and saliva towards the stomach. (The progression of the muscular contraction through the esophageal body is referred to as a peristaltic wave.). By the time the peristaltic wave reaches the lower sphincter, the sphincter has opened, and the food passes into the stomach.

In achalasia there is an inability of the lower sphincter to relax and open to let food pass into the stomach. In at least half of the patients, the lower sphincter resting pressure (the pressure in the lower sphincter when the patient is not swallowing) also is abnormally high. In addition to the abnormalities of the lower sphincter, the muscle of the lower half to two-thirds of the body of the esophagus does not contract normally, that is, peristaltic waves do not occur, and, therefore, food and saliva are not propelled down the esophagus and into the stomach. A few patients with achalasia have high-pressure waves in the lower esophageal body following swallows, but these high-pressure waves are not effective in pushing food into the stomach. These patients are referred to as having "vigorous" achalasia. These abnormalities of the lower sphincter and esophageal body are responsible for food sticking in the esophagus.

Hepatitis G

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 48167

Hepatitis G is a newly discovered form of liver inflammation caused by hepatitis G virus (HGV), a distant relative of the hepatitis C virus.

HGV, also called hepatitis GB virus, was first described early in 1996. Little is known about the frequency of HGV infection, the nature of the illness, or how to prevent it. What is known is that transfused blood containing HGV has caused some cases of hepatitis. For this reason, patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions who require large amounts of blood or blood products are at risk of hepatitis G. HGV has been identified in between 1-2% of blood donors in the United States. Also at risk are patients with kidney disease who have blood exchange by hemodialysis, and those who inject drugs into their veins. It is possible that an infected mother can pass on the virus to her newborn infant. Sexual transmission also is a possibility.

Often patients with hepatitis G are infected at the same time by the hepatitis B or C virus, or both. In about three of every thousand patients with acute viral hepatitis, HGV is the only virus present. There is some indication that patients with hepatitis G may continue to carry the virus in their blood for many years, and so might be a source of infection in others.

Hepatitis E

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 44122

Hepatitis E is an illness of the liver caused by hepatitis E virus (HEV), a virus which can infect both animals and humans.

HEV infection usually produces a mild disease, hepatitis E. However, disease symptoms can vary from no apparent symptoms to liver failure. In rare cases it can prove fatal, particularly in pregnant women.

Normally the virus infection will clear by itself. However, it has been shown that in individuals with suppressed immune systems, the virus can result in a persistent infection which in turn can cause chronic inflammation of the liver.

Hepatitis D

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 47770

Hepatitis D, also known as the delta virus, is an infection that causes the liver to become inflamed. This swelling can impair liver function and cause long-term liver problems, including liver scarring and cancer. The condition is caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV). This virus is rare in the United States, but it’s fairly common in the following regions:

- South America

- West Africa

- Russia

- Pacific islands

- Central Asia

- the Mediterranean

HDV is one of many forms of hepatitis. Other types include:

- hepatitis A, which is transmitted through direct contact with feces or indirect fecal contamination of food or water

- hepatitis B, which is spread through exposure to body fluids, including blood, urine, and semen

- hepatitis C, which is spread by exposure to contaminated blood or needles

- hepatitis E, which is a short-term and self-resolving version of hepatitis transmitted through indirect fecal contamination of food or water

Unlike the other forms, hepatitis D can’t be contracted on its own. It can only develop in people who are already infected with hepatitis B.

Hepatitis D can be acute or chronic. Acute hepatitis D occurs suddenly and typically causes more severe symptoms. It may go away on its own. If the infection lasts for six months of longer, the condition is known as chronic hepatitis D. The long-term version of the infection develops gradually over time. The virus might be present in the body for several months before symptoms occur. As chronic hepatitis D progresses, the chances of complications increase. Many people with the condition eventually develop cirrhosis, or severe scarring of the liver.

There’s currently no cure or vaccine for hepatitis D, but it can be prevented in people who aren’t already infected with hepatitis B. Treatment may also help prevent liver failure when the condition is detected early.

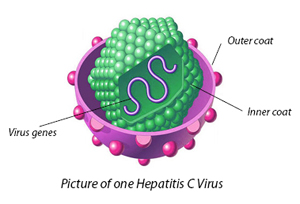

Hepatitis C

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 45062

Hepatitis C is a viral infection that causes liver inflammation, sometimes leading to serious liver damage. The hepatitis C virus (HCV) spreads through contaminated blood.

Until recently, hepatitis C treatment required weekly injections and oral medications that many HCV-infected people couldn't take because of other health problems or unacceptable side effects.

That's changing. Today, chronic HCV is usually curable with oral medications taken every day for two to six months. Still, about half of people with HCV don't know they're infected, mainly because they have no symptoms, which can take decades to appear. For that reason, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a one-time screening blood test for everyone at increased risk of the infection. The largest group at risk includes everyone born between 1945 and 1965 — a population five times more likely to be infected than those born in other years.

Hepatitis B

- Category: Gastroenterology

- Views: 44819

Hepatitis B is a serious liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). For some people, hepatitis B infection becomes chronic, meaning it lasts more than six months. Having chronic hepatitis B increases your risk of developing liver failure, liver cancer or cirrhosis — a condition that causes permanent scarring of the liver.

Most people infected with hepatitis B as adults recover fully, even if their signs and symptoms are severe. Infants and children are more likely to develop a chronic hepatitis B infection. A vaccine can prevent hepatitis B, but there's no cure if you have it. If you're infected, taking certain precautions can help prevent spreading HBV to others.